Introduction: What Are Data Centers and Why Are They in the Spotlight?

Few topics have captured the attention of economic developers and the public recently like data centers. Once considered back-end infrastructure, they’ve become front-page news and a focus for elected officials, utility providers, site selectors and communities across the country. Some communities are racing to attract these massive digital facilities that power cloud computing, artificial intelligence, streaming, and e-commerce.

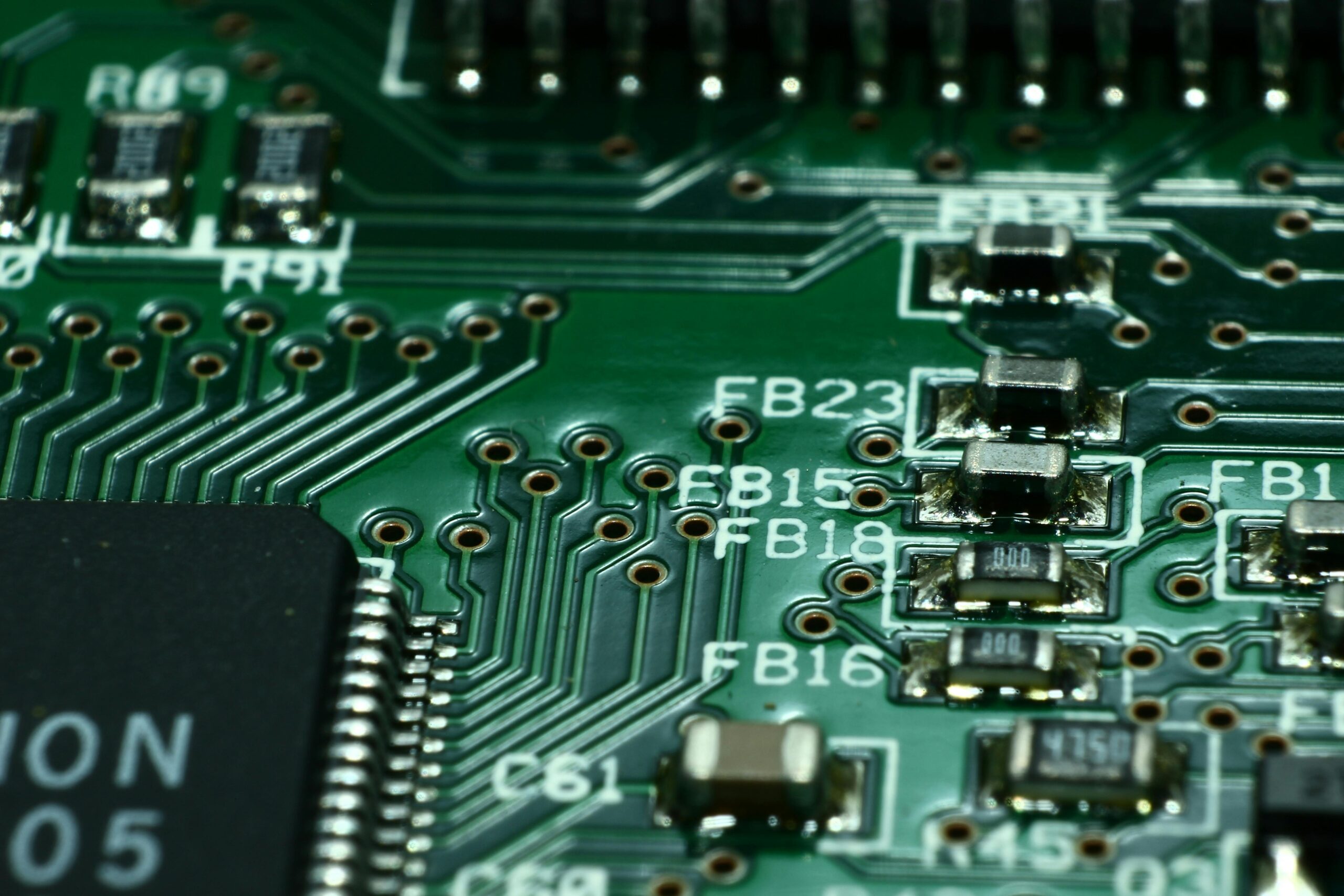

At their core, data centers are the physical backbone of the internet. They are warehouses filled with thousands of servers that store, process, and transmit the world’s digital activity. But data centers are also large industrial facilities that require vast amounts of electricity, water, fiber, and real estate. As the digital economy expands and AI workloads grow, the pressure to build new capacity has grown, along with competition among some regions to host it.

That race has turned data centers into a potential economic development win and generated heated political discourse. Supporters see them as engines of investment and fiscal stability. Critics worry about costly tax subsidies, environmental strain, and limited job creation. The real question is not whether data centers matter, but whether they represent smart and sustainable economic development for the communities that attract them.

What Is the Opportunity Cost?

Every economic development decision involves trade-offs, and few projects make those choices clearer than data centers. Economic development can often be described as an analysis of local and regional opportunity cost and the best economic developers in the country excel at this analysis. Behind the big headlines are real questions about how communities use their most limited resources: land, power, water, and public revenue. Once those resources are committed to a facility that uses a lot of them but employs few, they are no longer available for other priorities such as housing, advanced manufacturing, or small business growth.

That is the essence of opportunity cost—what a community could have built instead. Data centers often require major infrastructure investments: new grid capacity, fiber extensions, road and utility improvements, and tax incentives that can add up to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Not all trade-offs are losses, however. When structured carefully, data center projects can jump-start critical infrastructure that benefits entire regions. Expansions by Google and Meta in Iowa’s Des Moines metro and by major hyperscalers in Georgia’s Newton County led utilities to upgrade substations and fiber routes. Those improvements now serve other businesses and residents as well. In these cases, the data center became the first major customer, helping to make projects financially feasible that might not have been built otherwise.

There is also a forward-looking benefit. As industries rely more on artificial intelligence, automation, and real-time analytics, proximity to computing capacity could become a key advantage in site selection. Cities such as Phoenix, Dallas–Fort Worth, and Northern Virginia are promoting their large data center clusters as magnets for manufacturers, logistics firms, and digital companies that want to be close to the cloud. Today’s data centers may be tomorrow’s industrial parks. Instead of rail lines and highways, their assets are fiber, cooling, and computing.

That potential comes with caution. The Northern Virginia Technology Council has found that data center incentives are among the costliest in the country, averaging about $1.95 million per permanent job. Yet in regions where the ecosystem is mature, such as Loudoun County, Virginia, the return can be remarkable. Loudoun earns more than $26 in tax revenue for every $1 it spends on public services related to data centers, according to the Loudoun County Economic Development department.

The key question is not whether data centers are good or bad. It is whether they represent the best use of a community’s finite resources, and whether they leave behind infrastructure that future industries can build upon.

What are the trade-offs for communities?

The Upside

- Large and fast investment. Hyperscale projects can pour hundreds of millions of dollars into construction and equipment, supporting trades jobs and suppliers even if long-term job counts are modest.

- Durable fiscal base. Equipment-heavy facilities can provide steady property and business personal property tax revenue, helping to stabilize local budgets.

- Indirect benefits. Data center clusters often drive upgrades to the power grid, dark fiber, and substations that later benefit other businesses and residents.

The Downside

- Few permanent jobs. Operating teams are small relative to the investment, and studies find limited evidence of local wage growth once construction ends.

- Grid and rate pressure. The International Energy Agency projects that global data center electricity use could double by 2030, raising concerns about capacity and costs for other customers.

- Land-use conflicts. Substations, high-voltage lines, and large windowless buildings can conflict with nearby residential or mixed-use developments, limiting higher-employment opportunities.

Data Centers in Kentucky

The question of data center development is not hypothetical—it is happening now in Kentucky. The commonwealth offers affordable land, reliable utilities, and proximity to major fiber routes, which makes it a strong contender for future hyperscale and edge computing projects. With nearby metros like Columbus, Nashville, and St. Louis already attracting large data center investments, Kentucky is increasingly part of that conversation. But readiness is not the same as inevitability. Whether data centers become a long-term asset or a missed opportunity depends on how local elected officials and state policymakers shape the rules of engagement. Tax exemptions, utility rate structures, and zoning ordinances are not just administrative tools; they determine whether a project creates lasting community value or simply passes through.

Kentucky has updated its tax code to remain competitive, but legislators face a careful balance. Incentives must be large enough to attract investment without undermining local tax bases. Neighboring states show both outcomes: Virginia’s fiscal success in Loudoun County on one side, and smaller localities elsewhere struggling with long abatements on the other. The structure of state incentive law will largely decide which path Kentucky follows. Local governments hold the most direct influence. County fiscal courts, utility partners, and planning commissions can negotiate infrastructure agreements, manage zoning impacts, and require transparency around energy and water use. They can also set expectations for community benefit agreements, sustainability goals, and performance-based incentives that match Northern Kentucky’s long-term growth strategy.

When handled thoughtfully, data centers could strengthen a region’s infrastructure network, catalyze utility upgrades, and position the community as a meaningful node in the digital economy. If handled poorly, they could strain the very systems that make the region attractive. The challenge for Kentucky’s policymakers is to write the playbook now—while they still have leverage—rather than after deals are already in motion.

In the end, the story of data centers in Kentucky will depend less on the companies that arrive and more on the policies and partnerships that welcome them. Success will rely on whether local and state leaders can align around a clear strategy that protects public resources, maintains fiscal health, and ensures that the infrastructure built for data today serves people and businesses well into the future.

Ashby Drummond is Research Analyst for BE NKY Growth Partnership.